Have you ever tried to play a top E on a bassoon? Sorry, silly question. Why would you want to?

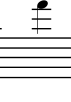

I had to do it recently. Look, here’s a top E in the bass clef:

It has ledger lines. A ridiculous number of ledger lines. Am I a flautist? No.

Here it is in the tenor clef. This is supposed to make it better.

Frankly, it doesn’t help.

Now, I’m going to be completely honest. When I was confronted with that note, for the first time since the age of about 12 I felt utterly bewildered by my own instrument. I realised that I had no idea how to play a top E on a bassoon. Never before has it been remotely necessary.

So I looked it up on the internet.

It would appear that there as many ways to play top E on a bassoon as there are stars in the sky. There are numerous websites explaining how to do it. None of them agree. This was not encouraging.

Anyway, I tried. I really did. For 7 days I attempted my top E, looking up various ways on the magic interweb to reach an absurdly unnatural register on what is, essentially, an instrument not designed to go there.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Which composer required me to make this much effort?

Ravel. His piano concerto in G major, if you’re interested in such things. Well yeah, exactly. Ravel was French. He wrote his bassoon part for a French bassoon.

Have you ever heard a French bassoon? No?

OK, imagine a whiny person whining about something or other… with a bad cold. That’s what a French bassoon sounds like. This is why most sensible people don’t play French bassoons – or `bassons’, as I believe they’re called in classical music circles.

Put it this way. The only thing going for a French bassoon (sorry, basson) is that they can play high notes. Stupidly high notes. The ones that most bassoonists clench their buttock muscles and say a prayer for.

You know the solo at the beginning of The Rite of Spring? Yep, it was written for a French bassoon. And apparently, the bassoonist had a spot of bother with it. I reckon it was that poor sod who started the riot. It saved embarrassment.

I play a German bassoon. Most of the time I’m told it sounds rather lovely. My neighbours, during those 7 days attempting my top E, will tell you that it sounded like a constipated cow trying to pass a baseball.

In the end I gave up and played it down the octave. Nobody noticed.